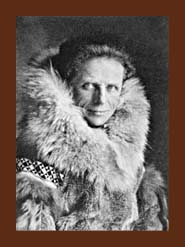

LEONHARD SEPPALA WAS BORN in Skibotn, Lygenfjørd, Norway -- 600 miles north of the Arctic Circle -- the 14th September in the year 1877. His family moved to the village of Skjervøy two years after his birth. His father was both a blacksmith and a fisherman. As a child Leonhard did farm work, keeping the family homestead going while his father was away on the fishing grounds. He began to go in his father's fishing boat the "Leviathan" at the age of twelve, and also apprenticed in his father's smithy. It was a demanding and rugged life for a child; "Sepp" (as many later called him) grew up tough and self-reliant. Each year until 1897 he went to the Finnmark fishing grounds. At the age of twenty he went to the city of Kristiana (now called Oslo), where he worked at the smithies there until he completed his "masterpiece" in December 1898, the project (a hand-forged vise) that would demonstrate his competence at the trade and allow him to work as a Master blacksmith. After the death of his childhood sweetheart Margit, whom he had planned to marry, Sepp returned to Skjervøy to work in his father's smithy.

THE GOLD STRIKES IN ALASKA and the Yukon were the talk of Norway around 1899. Seppala's friend Jafet Lindeberg returned home from Alaska flush with gold dollars and encouraged Sepp to take ship for the gold fields, even offering to lend him money for his passage. In 1900 Sepp succumbed to the lure of gold; on the 14th June he arrived on the S.S. Ohio in the city of Nome, where Lindeberg had his Pioneer Mining Company. He then had to learn mining from the ground up, starting out driving horses and a wagon (which he had never done), filling a slip scraper to clear the sluice boxes, and shoveling gravel on Discovery Claim at Anvil Creek. The Scandinavian miners, including Sepp's employer, had constant problems with claim-jumpers and shyster lawyers, all of whom were determined to do the foreigners out of their claims and take them over. Lindeberg was a leading figure in the immigrant miners' fight for their rights, and Sepp, as a Pioneer employee, was involved in a number of hair-raising adventures in defense of Pioneer claims against claim-jumpers.

Eventually Sepp got his chance to go prospecting for the company. He writes:

"One day Lindeberg came to me and asked me if I would go on a prospecting trip. The pay was ten dollars a day. I accepted readiy, glad to escape the steady grind with the shovel. I was by far the smallest man in the gang, and it was hard to keep up with the big, raw-boned Irish and Scandinavians, with many of whom shoveling was a profession."This first trip up the Nome River into Gold and Slate Creeks was with a party of eight men and eleven horses. When the rain started in September, they went back to Nome, and Sepp resumed shovelling, which caused him considerable suffering and hardship. He writes:

"With the approach of evening I thought of the little shop in Norway and regretted that I had listened to the golden-tongued orators who had persuaded me to come to Alaska. But I had only myself to blame. I wanted adventure, and I was getting it. [ ... ] Life in Norway never seemed so sweet as when I toiled away the dark rainy nights shoveling [ ... ] we at least had ground under our feet, and not hundreds of fathoms of roaring Arctic Ocean."The following December word came of a strike made up in the Kougarok. Lindeberg offered to send Sepp as part of a party to stake claims there. Sepp went along with his Swedish co-workers John, Andrew and Fred with two dog teams -- the beginning of Sepp's career with sleddogs. Sepp's first two sleddogs, Jack and Nigger, 110 and 120-pound black mongrels, came from this group. He describes these two as "splendid animals," saying that they "pulled loads that would have staggered ordinary dogs."

SEPP WAS A VERY SMALL MAN, short in stature and light in physique, but quite athletic. He had learnt to wrestle as a boy, virtually as a matter of self-defense. Although he found the heavy labour of Nome mining gruelling with its endless mounds of gravel to be shoveled, he was very fit. Of course, Norwegians of the far north are almost born on skis. He writes:

"During the daytime I did a lot of skiing. Skiing was becoming the one sport of the day, and there were races and jumping contests patterned on those in Norway. I had skied all my life, and had little trouble competing against the novices. In those days the skiing held the importance later usurped by the dog racing; it absorbed the interest of the public, increased the skill of the beginners, and eventually attracted experts from all over Alaska."Sepp actually beat a recently-arrived ski-jumping champion from Norway, to the consternation of his rival, and was also a keen competitor in the races. He tells the tale, too, of being asked to fill in at a wrestling match for a competitor who had "given out," only to discover himself matched against a man who outweighed him by thirty pounds or more. Unfamiliar with the wrestling holds used locally, Sepp was apprehensive, tested his opponent out and found him on the slow and clumsy side, then when he was rushed, saw his opening and threw his opponent to the floor and pinned him. When the referee parted them, it was discovered Sepp's opponent had sustained three broken ribs. Sepp wrote: "It was an unlucky throw, and I was as surprised as he at what I had done, and exceedingly sorry that I had been so violent."

WHILE SEPPALA WAS IN ALASKA the sport of dogsled racing was developed as a winter recreation; in 1908 the first All-Alaska Sweepstakes race was run. The following year a team of ten sleddogs was brought to Nome from eastern Siberia by a Russian fur trader. They were laughed at and given 100-to-1 odds due to their size, which was only half that of typical Alaskan sleddogs of the day, yet they almost won an upset victory at the second Nome Sweepstakes race in 1909. (It was widely rumoured that the team had been interfered with or the driver bribed by gamblings interests; at such odds, had the team won the race it would have broken the Bank of Nome.) The following summer a shipload of seventy Siberian dogs bought at the Siberian trading village of Markovo on the Anadyr River were imported by a wealthy young Scot, Charles 'Fox' Maule Ramsay, second son of the Earl of Dalhousie. The Ramsay import dogs, from which three racing teams were fielded, dominated the 1910 third All-Alaska Sweepstakes, placing first, second and fourth. The same year the AAS was first run, 1908, Seppala married his wife Constance, a Belgian girl who had come to Nome in 1905.

IN 1913 SEPPALA'S EMPLOYER Jafet Lindeberg, a mining company operator,

entrusted him with the raising and training of a group of Siberian

females and puppies, about fifteen dogs in all. 'Sepp' entered the 1914

Sweepstakes with this team but failed to finish the race after getting caught

in a blizzard and nearly going over a two-hundred-foot precipice along the

Bering Sea coastline.

The following year Seppala's Siberian team won the Nome

Sweepstakes. Seppala dominated Alaska's major race thereafter, winning

consistently with his Siberian sleddogs until the race was discontinued

during the First World War. Seppala continued to import, breed, and train

Siberian sleddogs, becoming a legend in his own time. Those who raced

unsuccessfully against him claimed he had hypnotic powers of control over

his dogs, so unbelievable was the performance of the Siberian dog teams

he drove.

Seppala had dogsled racing psychology down pat as well. In 1916 the Nome Kennel Club was challenged by the Ruby Kennel Club. The native drivers from the Yukon River had a reputation of being extremely tireless and possessing fast teams; none of the Nome mushers wanted to accept the challenge. Sepp decided to give it a try, but was appalled on his dogsled trip to Ruby when a native with a crosscut saw appeared out of nowhere and trotted easily alongside his sprinting team, keeping pace effortlessly. Once the race was under way, Sepp writes:

"I was told that the course lay over three high hills and that the Indian drivers ran like deer up the mountains on foot ahead of their teams. This did not sound very encouraging. [ ... ] For a while I let the fast teams keep just ahead, and then I gradually gained on them, passing them one by one. I wanted to have a little fun, so I sat down in my sled, lit a big cigar, leaned back comfortably, and smoked away as if I were out for a pleasure jaunt. But what the men behind me did not know was that I was driving hard just the same, urging my dogs to greater effort as I sat there. I soon left the others behind, and succeeded in winning the race by fourteen minutes, thus establishing a new record."Later he overheard one of the drivers complaining, "He just sat in his sled smoking a cigar while his dogs walked away from us as fresh as though they just started." That evening, in a saloon with the other drivers, he was confronted by one of the gamblers who had lost money on the outcome of the Ruby race:

"I saw a small man about my own size. He looked me over from head to foot, then nodded his head up and down, saying to me: 'So that is all there is to you -- and still you got away with my twelve hundred dollars with those little plume-tail rats of yours! [ ... ] I am a small man myself, but always admired big men and big dogs, and it has cost me twelve hundred dollars to learn that it is not always size that wins.'"Seppala's leaders for the Ruby race (before the "Togo" era) were Scotty and Jens, neither of them terribly big or tall dogs.

Leonhard Seppala leader Bonzo

IN 1925 THE CITY OF NOME was threatened by a midwinter diphtheria epidemic. Seppala became the crucial figure in the delivery by dogsled of a supply of antiserum via an otherwise impassable route between Nenana and the stricken city. Seppala set out from Nome, met the driver carrying the serum from Nenana more than halfway, and returned immediately by night across Norton Sound, traveling 340 miles over treacherous sea ice and through blizzard conditions to bring the serum back. (Other relay teams involved in the delivery included that of Gunnar Kaasen who made the final leg with cull dogs of Seppala's that he had left behind; none of the other teams made more than 53 miles of travel at most.)

The leader of the Serum Drive team had been Togo, and Sepp was outraged at the publicity given to "newspaper dog" Balto who had led the Kaasen team, feeling that the credit had been stolen from Togo who had deserved to be considered the hero of the run. Also along on the Serum run was the ageing Scotty. Sepp states that the Serum Drive was Togo's last long run, and that in that drive he had worked his hardest and best. If the Serum Drive finished Togo, it must have been harder yet for Seppala's old Sweepstakes leader.

The following year, on the strength of publicity consequent to the Nome Serum Run, Seppala embarked on a tour of the 'Lower 48' with 44 dogs and an Inuit handler. His tour finished in the State of Maine in 1927 with a challenge race in Poland Spring against Arthur Walden, breeder of 'Chinook' dogs and author of A Dog-Puncher on the Yukon. Seppala won the race, and afterward started the first historic 'Seppala Kennels' in Poland Spring in partnership with a former driver of Chinooks, Mrs. Elizabeth Ricker.

SEPP AND LIZ RICKER were a feature on the eastern race circuit from 1927 through 1930. He won the New England race, the Lake Placid Race, and the Poland Spring event three years running. In 1929 he won the Eastern International Dog Derby in Quebec City, setting a new trail record for the three-day 123-mile event with "Bonzo" at single lead. (Victory at this race had eluded him the two previous years and he was determined to win it in 1929.) In many of these races Liz Ricker raced the second team and often came in right behind Seppala; in fact, she won the Poland Spring race in 1930, also with Bonzo at lead, again setting a new trail record for this three-day 75-mile event. Seppala's worst competition during this entire period was the Quebec driver Emile St. Godard, who bested Seppala to win the Olympic Demonstration dogsled race at Lake Placid, NY, in 1932, which was Seppala's last race in the East.

Seppala gave the ageing Togo to Liz Ricker so that his old leader could enjoy a pampered, comfortable retirement. Sepp wrote:

"It seemed best to leave him where he could be pensioned and enjoy a well-earned rest. But it was a sad parting on a cold gray March morning when Togo raised a small paw to my knee as if questioning why he was not going along with me. For the first time in twelve years I hit the trail without Togo."

Liz Ricker divorced her husband Ted and relocated, along with Seppala, to Grey Rocks Inn in St. Jovite Station, Quebec. At the New Year festivities at the resort in 1931 she met Kaare Nansen, the son of Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen, and very shortly thereafter married him and left North America to sojourn in Norway with her new husband. It remains unclear just what happened (rumours say that Seppala ran up a hotel bill at the resort that he was unable to pay), but at some point around this time the core Poland Spring stock that had gone to Quebec became the property of Harry R. Wheeler, the owner of Grey Rocks Inn. Seppala apparently remained in St. Jovite through the winter of 1931-32 and competed with his Siberians for the last time at the Lake Placid Olympic demonstration race.

SEPPALA'S EXPLOITS and the Poland Spring kennel breeding gave

a powerful boost to the early days of sleddog sport in New England. The

infant Siberian Husky breed, established in the USA in 1930, could hardly

have gone anywhere without the Poland Spring dogs and the sleddogs of

Wheeler, Shearer and the Belfords that were bred from them.

The acquisition in 1931 by Harry R. Wheeler of the three

Siberian imports Kree Vanka, Tserko and Volchok, together with other key

Poland Spring stock, marked the founding of the second historic Seppala

Kennels, which operated until 1950. The Wheeler dogs became the foundation

of the Seppala Strain that was finally registered by the Canadian Kennel

Club in Canada in 1939 as the 'Siberian Huskie.'

Seppala's direct involvement with the breed that now bears

his name was over, but his Seppala sleddogs, descendants of original Siberian

sleddogs from Chukotka, Kamschatka and the Kolyma River basin, had been placed

by him on a path that would ultimately lead to the birth of the Seppala Siberian

Sleddog breed in the 1990s.

Seppala had not abandoned his mining career with his tour of the U.S.A. After the tour was completed and his dogs safely settled in Poland Spring, he returned each spring to Alaska to continue his employment there, leaving the dogs in Liz Ricker's care. After 1932 he remained in Alaska. He was based in Nome for the first twenty-nine years of his mining career, twenty-three of them spent with the Pioneer company. Subsequently he worked as a ranger for U.S. Mining and Melting Company, first in Nome and then in the Fairbanks gold fields until his departure from Alaska in 1946. He then bought a house near Seattle, where many other Norwegians had also settled. For some years in Seattle in his retirement he had a partnership arrangement with the Bow Lake Kennels of Earl L. Snodie, "specializing in purebred white blue-eyed Siberians," as he wrote in 1947. In 1961 Sepp and his wife revisited Fairbanks and other places in Alaska at the invitation of American journalist Lowell Thomas, enjoying a warm reception from the Alaskan people. He lived in Seattle until his death on the 28th of January 1967 at the age of ninety. His wife Constance died a few years later aged eighty-five. Both are buried in Nome, Alaska.